Tony Sweet is a Nikon legend behind the lеns. Tony has worked as a professional jazz drummer for 20 years, playing with other great jazz artists such as Sonny Stitt and Joe Henderson. It was at this time, Tony began taking insightful photographs and capturing the essence of jazz clubs. He later refocused and honed in on nature photography. Now, he is widely known for his phenomenal skills in fine art nature and floral images.

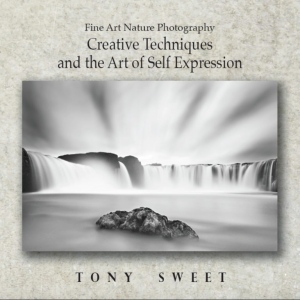

Get his new book “Creative Techniques and the Art of Self Expression“ here:

tonysweet.com/new-ebook-creative-techniques-art-self-expression/

Take a look at his gallery here: tonysweet.slickpic.com.

Read more about Tony in a fascinating interview that explains his journey from thriving musician to a world class photographer. Learn Tony’s personal tips and tricks in the video tutorials below.

You started as a jazz musician and magician, what drew you to those areas. How did you start in that and then transition to photography?

I started off as an accountant, actually. I felt like I was misplaced in my career and wanted to do something different. I was going to college for accounting and playing drums professionally so I didn’t get much sleep. After I finished accounting school I went to music school at Towson State University, known for its jazz program. Hank Levy, started the jazz program. I played in his band for a few years, playing on 2 recordings.

After a stint on the cruise ship circuit as a musician/magician, I moved to Cincinnati to finish my degree, then taught as adjunct faculty at the University of Cincinnati. During the cruise ship period, I met a girl who taught me handwriting analysis. I studied and became a certified grapho-analyst, which enabled to me to be called as an expert witness in a court of law. In the midst of all of the aforementioned activities, I traveled with the Great Harry Blackstone (world tour and on Broadway), where I picked up close up magic, which I performed professionally for a few years. I still practice when I have time.

This sounds a bit disjointed but, it was all happening in the same time frame. I was playing music, including on an HBO special and at the Seattle Opera House and performing magic, going table to table in restaurants. Then I spent a few years as a bike mechanic, enabling me to bicycle race, for a couple of years. I had also gotten interested in photography at the same time. The best time for the bike rides was at dawn which was also the best time for the photography so I had to make a decision. I decided on photography.

When just getting started, I was trying to save money, so I looked for a good used camera gear dealer. That’s where I met my first mentor, Tony Gayhart, who had a small camera repair shop in Union, KY. He was patient and generous with his time. His advice was a rock solid foundation.

For 18 months, I would get in at 3 am from playing music and wake up at 6 am to go to the Cincinnati Nature Center to photograph. I would go home and process the transparencies. I had a Jobo and everything for processing transparencies. Then I would call up Tony and drive 40 miles to his house to show him my slides and he would critique them. “Use a warming filter,” “compose it this way,” “get higher, get lower.” I would take notes and the very next morning go out and correct everything. This went on for a year and a half. You can’t buy that kind of education. Private tutoring every day for a year and a half. I was able to fine tune my work.

About this time Bill Fortney was sending out information for the Great American Workshops. He was going to all the places I wanted to photograph: the desert southwest, Acadia, Grandfather Mountain, etc. On a lark, I sent Bill a page of slides, hoping to be considered to come along as a gopher. A month and a half went by and I was beginning to think that I would not hear from him when he left a message on my answering machine that he would love to have me come along. I didn’t expect to get paid, but figured that I had 10 thousand dollars saved up and thought of this as my photography education. I used the money on travel and rooms following Bill around for about 2 years. He would bring in Galen Rowell, John Shaw, John Netherton, Jim Brandenburg, Rod Planck, etal, all of the nature photographers we looked up to in those days. I was co-teaching with these guys, and I was thinking this is unbelievable. I asked a ton of questions and learned a ton!

After a while I moved on and moved back home to take care of my parents and started giving presentations to camera clubs. I was still playing music at the time, but felt that I would eventually be moving into the nature photography business. People knew the photographers who were giving the Fortney workshops and I was part of that, so it got me in the door at a lot of places. I talked to the clubs and started offering workshops. I would take out one person. I never canceled a workshop. I would have one person then the next time it would be 3 or 4 and I realized it was a building process. There is no overnight success. It takes time. You pay the price for a while until things start coming your way. I didn’t have the maturity to understand that when I was younger, but I had when I embarked on my photography career.

I had some good breaks. About that same time, Shutterbug did a feature article on my nature photography. I knew the editor from Nikon and Nikon World and through his relationship with Shutterbug I started writing articles for Shutterbug. My father was still alive then and he finally got to see what I was doing and begin to think I was going to amount to something before he passed.

I kept writing and wrote about a dozen articles for Shutterbug and then went to Nikon World and wrote for them until they folded. I also was a contributor to Rangefinder magazine. That’s how I began to reach a large audience, not through lectures, but through print media. This was how we got the word out before the internet and social media: no Facebook, no Twitter. Hard to believe it wasn’t that long ago.

I began to get a good reputation and the workshop registrations and requests to speak and teach began to pick up. Now, it’s a two person business with life and business partner, and outstanding photographer/teacher, Susan Milestone who is largely responsible for our growth over the past decade.

Now here I am with you as a featured speaker at the 1st Smoky Mountains Summit. It’s a nice place to be right now. I’m getting older and wonder how long I can do this. I’ve been doing it for 25 years now. If you like what you do, you never work a day. I can’t climb mountains anymore. I don’t even want to. Places like the Smokies, Acadia, and Charleston, for example, are very user friendly. These are great venues where I can photograph and teach as long as I want. I’m thinking about scaling things back in the next five years or so, but I feel great and love what I am doing so what more could I ask for.

Infrared by Tony Sweet

That was a great description of what it takes to build a career. What did you think of the transition from music to photography?

It is the same mind set. When I improvise music, the equipment is second nature and I am spontaneously reacting to quickly changing situations. It’s exactly the same thing in nature photography. One has to learn the tools until they are second nature. I react to light. I try to find my compositions quickly, work the area a bit, then move on. Psychologically there is no difference. I’m in the moment when I play music and I’m in the moment when I shoot.

I have noticed that a lot of photographers came from a music background. One seems more auditory and one seems more visual. What do you think is the affinity between those two arts?

It’s the same brain. I approach them the same. There is no difference. Musicians have a proclivity for math. I did math in my spare time. I enjoyed it when I was a kid. I bought books to work the problems, geometry and advance algebra in my spare time. They probably co-exist in some photographers because there is an intense technical element free thinking aspect to both. There is a lot of information that you have to have access to instantly. Since you can’t think as fast as you react, the equipment has to be second nature.

Tony demonstrates the use of a tilt shift lens in the Great Smokey Mountains National Park.

I believe your education in photography was based more on mentors than formal training. Who were your early mentors and what did each one instill in you?

I don’t know how, but I have always been lucky. To paraphrase a Zen expression, “When the student is ready, the teacher appears.” That is how things worked out for me during my music career, my short magic career, and in my photography career.

As a professional drummer, I was on the national tour and on Broadway with the great magician, Harry Blackstone, Jr. We began playing backgammon on the breaks during the shows, but it evolved to Harry teaching me elements of close up magic. When the tour ended, Harry recommended a magician/ teacher in Baltimore and that’s when I met the great Cy Keller. Cy is passed many years ago now, but when we got together every Monday for about a decade, we continued the backgammon tradition, peppered with magic lessons, and an education in jazz, playing music during our weekly visits. A great teacher will teach you concepts and lessons that apply universally. For instance, he taught me how to be economical with movement, which applies to magic, music, and photography.

I like learning things that span all the disciplines. Many things apply everywhere. That what I like picking up from all these different disciplines. Pat O’Hara is phenomenal; one of my great mentors. I still look at his books today and even after having them for 20 years I see things I never saw before. The way that he created images draws your eyes to a given area, and you are so riveted that you never get away from that area. It is almost like subterfuge. There are layers and layers to the composition, and it can take a long time to discover them all. I had an affinity for Pat’s work. When I hit my stride as a photographer, it was Pat O’Hara and Freeman Patterson who were in my uppermost thoughts. The visceral nature of their work was and still is a profound influence on me. Now, I can find inspiration in many photographers, pros and non-pros alike. Everyone has a point of view from which we can all learn.

Cole Thomson has an idea he refers to as “Photo Celibacy.” He tries to avoid looking at the work of others in order to avoid being influenced. Some musicians didn’t want to listen to anyone else. They wanted to develop their own style. That is hard to do unless you are gifted. If you are gifted, you can eschew everyone else and go your own way like Picasso or John Coltrane. Most of us, on the other hand, need a foundation, and studying the work of others is how most of us start. Then, after a few years, your a personal path may begin to emerge. You can’t unring a bell. When I see someone else’s composition, it gets in my head. It’s someone else’s shot. At this stage of the game, I don’t want anyone else’s image. It used to bother me. I would see a good shot in a workshop, and I would want to do it right away. The last time I copied a student’s image was about 20 yrs ago. I had a website then and put the image online. As soon as I posted it, I took it down immediately. It wasn’t my shot.

From that point forward, I learned to find your own work. Now, if I see a shot I like a lot at a workshop, I file it away for a year. When I come back a year later, it will not be the same shot.

Every shot is essentially a self-portrait. The longer one does anything, the more personal the work gets.

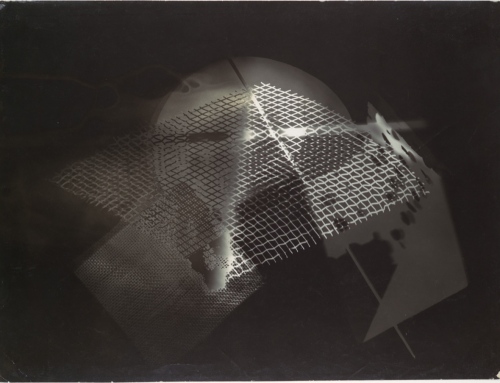

PlanetOwanka by Tony Sweet

Looking through your folios, your work is about as varied as anyone’s I’ve seen. Sharp and soft focus. Macro and landscape. People and Buildings. Long and multiple exposures. Straight photography and added textures and effects. Color, black and white, and infrared. Big camera and iPhone. Maybe there is generally a theme of color and texture in common. Many photographers only show one style on their website. What draws you to take and share so many different types of images?

Basically, it the way that I’m wired. John Shaw was called a macro photographer for 20 years, and he would say he did everything. They had John Shaw pigeon holed. I try not to do that to myself. I’m not sure what style means. There is this whole movement toward workshops on developing a personal style. That’s ridiculous. Style is a product of our lifetime. You can’t just take a course and in one week say this is my style. What if I say my style is this, but someone else says my style is that? Who’s right? Other people are at least a part of defining your style.

As far as my eclectic portfolio, someone asked the great Duke Ellington what was his favorite kind of music. He replied saying that was two kinds of music, good and bad. I think there are two kinds of photography, good and bad. I like good photography. The subject material is widely varied. Do I like nature photography? Sure, that is where I started. If I had to pick one right now, it would be infrared. Today, I am shooting about half color and half infrared. Things run their own life course; I’m just along for the ride. Then I will do whatever comes next.

Do you have a preconceived notion of what you are going to shoot or do you explore and shoot what you find?

Ninety percent of the time I just open my mind to whatever gets my attention, conscious and sub-conscious. Occasionally I have a preconceived notion of what I want to shoot and go looking for it. I don’t always get it, but something else will show up. One mistake people make is being destination driven. Many times there is a good shot on the way to the destination. What if I see a great fog on the way? I will shoot the great fog and go to the destination later. Almost without exception, if I pass up a great shot to go on to where I was going, the shot I passed up was better.

When you go out to shoot, what goals do you have for your images?

Something that feels right. If you don’t feel what you are shooting, no one else will either. I look for things that move me emotionally, things that excite me. Of course, photography is not what it used to be. Composition is always paramount, but now, all the camera does is capture raw material. A raw file is just a set of numbers. You can’t even print a raw file. You have to convert it. Unless I’m in the middle of phenomenal light, which doesn’t happen that often, I’m thinking in terms of what I will do after I get back and work with the file (exposure, contrast, saturation, creative processing, adding textures). The initial capture is raw material like something I can pour into a form and reshape. Traditional and creative use of editing software is essential in modern day digital photography.

Looms by Tony Sweet

When you are pleased with an image that you capture, how is it different than a competently captured, good image? What elements make it special for you?

First and foremost, strong, compelling, composition. Then, a good histogram. That’s it.

Do you have any favorite images and stories that go along with them?

Not exactly, but I have a recent experience. I improvised a 2 hour lecture at a recent event in Burlington, ONT. The topic was “Personal Style.” I walked in like a jazz musician not knowing what I was going to say along with a slide show. It occurred to me that I was doing a self-discovery session in front of an audience. As I ran through the images over and over, it became apparent that certain images remained in my mind more than others. As I weeded through the images, the ones that I consistently saved had a strong element of “One.” i.e. single tree, single rock, single cloud, etc.

Then I digressed into my childhood. I was an only child. Most jazz musicians, most nature photographers, most astronauts are only children. What do they have in common? It’s the ability to come to terms with life alone, it’s the ability to avoid boredom by creatively occupying ones self. I find that it is usually one thing that gets my attention, a single cloud or a single bicycle rather than a big landscape. If I were to define my own style, a constant theme/ element would be the solitary thing: one tree, sparse landscape, one ray of light. Things that are solitary. I think it is reinforced or comes from that only child background.

Tony and Sue demonstrate how to use printed backgrounds to create a soft bokeh effect around flowers.

What basic kit do you carry with you when you go exploring?

I work out of the car most of the time these days, which means that we work close enough to the car that going back to get something is rarely an issue. My infrared kit is a D800 converted for infrared with a 24-120mm lens. For color, the 14-24mm, which is a bit heavy, is optional, depending on where I go. The 16-35mm, 24-70mm, 70-200mm and the 105mm are always with me. I bought the Nikon 200-500mm for when I need to pull things in. For travel, like when I am in Cuba, I will take the 16-35mm and the 28-300mm and maybe add an 85mm f/1.4 for portraits.

In some of your early work, you used a lot of filters. Do you still use them now that you are digital, or do you use software to create the effects?

For adjusting white balance or adding magenta color I use software. You can’t polarize in software so I carry one of those. I do a lot of long exposures so I have 5, 10 and 20 stop ND filters. I use the Singh-Ray I-Ray which lets me shoot infrared with a color camera. I carry a UV filter for shooting in hostile environments like blowing sand, falling snow or under a waterfall. You don’t want to be constantly wiping off you lens or have glass hitting glass with the sand. I also carry split neutral density filters which you can imitate in software but I like the look the Singh-Ray filters give. For quick macro I have a Canon 500D to use on the 70-200mm for macro.

Lake Abiquiu by Tony Sweet

In what situation do you like to use you iPhone rather than you DSLR?

My iPhone photography goes in streaks. Right now it’s on the low side as I am working more on infrared. I use the iPhone because it is less intrusive and there are apps available on the phone that are not available in the computer. The phone is like a sketch pad. I always have the phone with me so I use it for spontaneity to take pictures of little things that I would never get the big camera out for. Then I can use the apps to give it more of an artistic rendering. More than anything, it just keeps your head in the game. The new iPhone 6 is 12 meg so when you put it into software with the 12 meg per channel it is a 36 megabyte file. Unbelievable. Matt Kloskowski said, and I agree with him, that all the technology is currently being put into small devices. All the kids coming up are writing code for the phone. Moment Cases have software built into the case and lens that attach. Rumor has it the iPhone 7 will be more of a camera with controls for the settings. That’s where it is obviously going. The sensor will still be small and noisy so I still like the D810. I have a D800 converted to infrared. But as far as the I-Phone goes, I’m sure I will get back into it more, soon.

It is pretty clear that you come down on the art side versus documentary photography. Can you talk a little about how much manipulation of the pixels you believe is acceptable?

Because of my jazz background, I’ve always thought of photography as interpretive, as a means of self expression. There are no rules. Whatever you can think of, try it. Photography is not what it used to be, and you lose a lot if you try to think the same way. There are infinite options available, which gives you a wider range of self-expression. We all want to stand out from the crowd. With the software tools available, we can bring that to fruition. Everything is alright with me. The pictures are in your head, not in the file, in the camera, or in the lens, or in the software. It’s in your imagination. The word manipulation has a bad connotation. I prefer the word “optimize.” But, I try to be careful that the effect doesn’t detract from the subject, although sometimes it’s ok.

What software products do you utilize to work with your images and what are the advantages of some of them?

I’m using Nik Viveza for color adjustment and Silver Effects for black and white. Macphun’s Creative Kit, Topaz, OnOne. Pick at least one of them and really learn it. The more you know about the various software products, the more efficiently you will get the effect you want.

I use Lightroom for basic processing. I use Photoshop when I need layers to combine images. It’s very perfunctory. After which, I’ll go into the aforementioned plugins to create a more personal interpretation.

Tony Kuyper’s Luminosity Actions is a very powerful selection and processing product. It allows us to target and optimize very specific, but non-contiguous parts of the image. Also, available and recommended are the instructional videos by Sean Bagshaw which are excellent 5 to 10 minute movies. They are both excellent teachers. Sean overlaps the material in the videos so that you keep getting exposed to it, and you can stop the video and go back over it.

Tony demonstrates how to use slow shutter speeds on water to create drama.

As varied as your images are the ways you offer education to photographers: Books, workshops, photo tours, seminars, on-line courses, individual mentorships, DVDs, and phone apps. What are some of the strengths and weaknesses of these methods of learning? How would you recommend that an advanced beginner to intermediate level photographer learn the skills and vision to get better?

You want to immerse yourself as much as you can. Given that most people have jobs and family they can not immerse themselves all day, every day. Attending a live workshop with a teacher that you want to immolate is one way. It’s like a direct injection of knowledge from a person you want to learn from. When you are on a workshop for several days, what you are learning keeps getting reinforced so you learn exponentially. To me, that is the most powerful way to learn.

You can couple that with a self-paced online course. As many different inputs as you can get given your lifestyle, the better it is. They cross pollinate each other. Buying and watching DVDs is a little like a workshop in a box. I don’t like to read a lot of photo books. I’m more visual and like to learn by watching and by looking and evaluating, but different people learn different ways. There is every possible option out there to get what you want out of photography depending on your learning paradigm.

Do you have recommendation on how a student should prepare for and participate in a workshop to get the most benefit from the experience?

First talk to the instructor. We get e-mails asking what to bring all the time. We provide a list that is half photographic and half human needs like layered clothing, water proof shoes, and bug spray. The photographic equipment suggestions include lens selections, filters, and editing software loaded on a computer.

Then think about what you want to learn based on what the teacher does. Ask how a certain effect was achieved, thought processes, compositional questions. Write the answers down so you will have them when you get home to practice. There may be notes given out or that you take, but you should leave with knowledge that transcends the notes.

Lupin field by Tony Sweet

What should a participant expect from the time he/she spends with you on one of your Visual Artistry Workshops?

The concerns of our clients is first and foremost. We help everyone in the field with subject selection, composition, gear questions, and answer questions. During afternoon class sessions, we critique images for immediate feedback, and demo software on client images.

We try to emphasize images in the Journal. To me, it seems your books do the same. They present an image and support it with a discussion of how to capture it rather than being a lot of text. How do you develop the concepts for your books and do you have more books planned?

Don’t you learn more from seeing the shot than talking about it? With early photo books in the beginning, I was always searching for image-relevant text, and have always wanted to see the image on one page of a spread and the text on the opposing page. As soon as I had the material, the books in my Fine Art Nature Photography series are all designed that way. Large image on one page and succinct, direct text on the opposite page.

In as far as new books, it’s a matter of time. I’m always tossing new book ideas around.

I have to ask, when did you start wearing the bandana?

Not exactly sure, but it’s been many years.

Are there any photographers that you think our readers should take a look at?

There are several on my website. In addition, Cole Thompson, Chuck Kimmerle, Michael Kenna, Jeff Birnbaum, John Sexton, Art Wolfe, Jay Maisel, Pat O’hara, Brenda Tharp, Jennifer Wu. A web search will turn up numerous, very talented photographers.

Any key piece of advice for the readers?

All of this technical stuff is great, but don’t forget to just have fun!

Photo by Tony Sweet

———

Tony Sweet’s newest ebook available to download now:

Creative Techniques and the Art of Self Expression by Tony Sweet

Creative Techniques and the Art of Self Expression by Tony Sweet

———

Share your memories in a beautiful online gallery

You’ve meticulously chosen your camera. You’ve pored over lenses. You framed your shots. Now, give your photos the attention they deserve. A beautiful gallery can make the difference between “So what?” and “Wow”. Get more “Wows” with SlickPic!